post by Andrew Williams, Imaging and Metadata Technician at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP)

This portrait, taken later in Deborah’s life, shows her wrapped in a traditional Quaker shawl and bonnet. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

One of the chief objectives of the In Her Own Right project is to showcase primary source material regarding Philadelphia women thinkers and writers in the century leading up to the Nineteenth Amendment. Among the most deeply intimate and reflective of the collections highlighted in the project is the diary of Deborah Norris Logan. The seventeen manuscripts that make up the memoir, which span the years 1815 to 1839, are a vista into the political events and day-to-day happenings of post-revolution America through the lens of Philadelphia’s Quaker elite. Deborah was an illustrious chronicler and avid antiquarian, though her role as a republican wife and mother was of primary importance to her.(1) Indeed, the sundry dimensions of Deborah’s character and her expansive literary interests are salient and persistent threads throughout the diary, and her writing delineates how women constructed their own identities within a broader social framework.

As historian Terri L. Premo points out, the life of Deborah Norris Logan was in many ways not one that was shared by most contemporary women.(2) She was born in 1761 to a prominent Quaker family. Her father, Charles Norris, was the son of Isaac Norris, a wealthy merchant and mayor of Philadelphia. While she attended Anthony Benezet’s Friends’ Girls’ School—the first public girls’ school in the country—she was primarily self-taught and created strict reading regimens for herself. In 1781 she married Dr. George Logan, a physician and politician who would serve as United States Senator from Pennsylvania. The Logan’s produced three sons, Albanus, Gustavus George, and Algernon Sydney. The family lived in Stenton, the Logan family estate in Germantown.

Deborah was a skilled and prolific writer. In addition to her diary, she wrote an annotation on the correspondence between William Penn and her husband’s grandfather, James Logan, which she discovered in the attic of Stenton. Logan modestly viewed the preservation of the documents as her duty:

“I have now partly determined to commence a work which will require both time and patience… it is to prepare for the press (or at least a copy for the Loganian Library) of the Letters and essays of James Logan, which I wish to preserve for posterity—not that I consider myself as qualified for such work, but that it has small chance of being performed unless I undertake it.”(3)

The Penn-Logan Correspondence was belatedly published by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1871. Shortly after George’s death in 1821, Deborah began writing a biography of her beloved husband. Her Memoir of Dr. George Logan of Stenton and her other writings helped confirm her status as one of the most eminent historians of Philadelphia, and in 1827 she was elected to be the first woman honorary member of the Historical Society.(4) She also produced a large repertoire of poetry, which can be found throughout her diary.

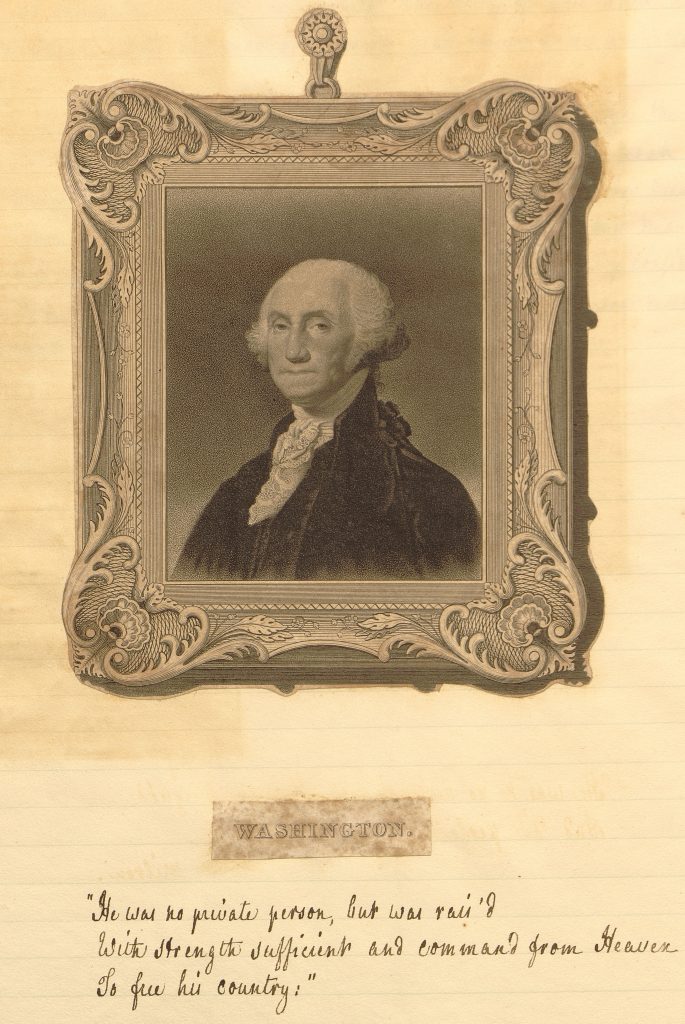

In her diary, Deborah called the first president of the United States ‘Great Washington,’ and gave an account of his visit to the Logan mansion, Stenton.

Logan’s social status afforded her access to America’s elite and foreign diplomats, many of whom would frequent Stenton, including John Adams, George Washington, and Joseph Bonaparte. Thomas Jefferson once implored George Logan to “assure Mrs. Logan of my constant and affectionate esteem and attachment the just tribute of the virtues of her heart and head.”(5) In addition to Deborah’s interactions with revolutionary dignitaries, the diary details her experiences at some of the most significant moments of the nation’s history, including the first reading of the Declaration of Independence. Deborah herself was often approached by local historians and editors for accounts of the Revolutionary War.(6)

Deborah considered herself an armchair traveler, and bespeckled her diary with newspaper clippings of exotic locales. Shown here is a contemporary image of Algiers, around the time of its annexation by France in 1830.

While Deborah possessed firsthand experience with American personages and events, she longed to see the world, and thought herself an armchair traveler. She relished her library and her sizable collection of antiques, and spent much of her time reading travel books and classical literature. Deborah shared her collections with members of her social circle and many acquaintances, and welcomed visitors who had been to the “Old World” themselves. In one instance, she recounts that she “…had a visitor who entertained me with his Travels in Egypt. If I were a young man I certainly would visit the remoter shores of the Mediterranean, and see the Old World for myself. I don’t think any body’s description can make you take in things quite like seeing.”(7) The exploits of James Douglas and the dramatic rise and fall of Napoleon also piqued Deborah’s interest. As Susan M. Stabile argues, Deborah’s reading was a form of curiosity collecting in itself.(8) Even her diary, which is inlaid with literary observations, clippings, and antique graphics, can be viewed as a commonplace book and repository. For Deborah and other antiquarians in the early nineteenth century, discovering and traversing history by reading was the medium through which the past could be recovered and preserved, and ultimately, the means of placing the nascent Republic in a wider historical context.

Deborah was particularly interested by the meteoric rise and fall of Napoleon Bonaparte. This clipping shows a romanticized scene of Napoleon’s tomb on St Helena, where he was interred before being transferred to Paris in 1840.

In addition to literary reminiscence and descriptions of political events, Deborah’s diary highlights the quotidian happenings of domestic life and her interactions with friends and family. She was completely devoted to her husband and her sons, and strove to live her life in accordance to Quaker and post-Revolutionary feminine values. In line with Quaker traditions, she rejected violence and disapproved of slavery. Her domestic duties were the first priority of each day, and even in her widowhood, Logan remained faithful to her husband and sought to preserve and honor his memory. Premo points out that, while Deborah continued to enforce the paradigm of a male-headed household after George’s death through her son Algernon, she scrutinized the role of the woman’s sphere and became more apprehensive towards male protection.(9) She was critical of women who did not take ownership of their own property before marriage, and when expressing her disapproval over a marriage she considered “hasty,” she censures the bride, stating “…she does not even secure her little property to her own use, foolishly trusting to his declaration that he does not want any thing to do with it.”(10) However, these musings did not seem to change her esteem for her role as a republican wife and mother.

Deborah was considered by her peers to be an exemplar of Quaker and Republican values, and the clippings of personified virtues found throughout her diaries perhaps reflect how she framed her own life.

As time passed, and following Algernon’s unexpected death in 1835, Deborah became reliant on her diary as an outlet for emotional distress. The last volumes paint Logan as oft alone and ever dependent on members of her family for support. She had difficulty reconciling what she saw as her duty to resign herself to the complications of old age with her social and literary pursuits.(11) Deborah also increasingly identified herself as a member of the Revolutionary generation. She scorned Andrew Jackson, calling him an “obstinate old General,” and was embittered by what she perceived as growing corruption in the United States government and a movement away from the Revolutionary values that she identified with.(12)

Deborah continued to maintain her diary until her death in 1839, at the age of eighty-two. Her writing makes it clear that Stenton was the center of her world. It was through the Logan’s mansion that Deborah moored herself to her family and the past, and served as a font of both stability and order. It was also a conduit through which she could pursue her literary interests and travel to distant lands where her age and sex would otherwise bar entry. Whether she was keeping her diary at the window facing the estate gardens or reading in her library, Deborah was a discerning yet quiet observer of the changes occurring around her. Indeed, for Deborah, Stenton itself reflected the synthesis of domestic and familial duty with romantic and historically-minded intellectualism that she herself embodied.

Ready to explore? Visit collections related to this exhibit in In Her Own Right: Deborah Norris Logan diaries in the Logan Family papers.

1 Terri L. Premo, “’Like a Being Who Does Not Belong’”: The Old Age of Deborah Norris Logan,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 107, no. 1 (1983): 86.

4 Marleen Barr, “Deborah Norris Logan, Feminist Criticism, and Identity Theory: Interpreting A Woman’s Diary Without The Danger of Separatism,” Biography 8, no. 1 (1985): 14-15.

6 Susan M. Stabile, “Female Curiosities: The Transatlantic Female Commonplace Book.” In Reading Women: Literacy, Authorship, and Culture in the Atlantic World, 1500-1800, ed. Hedi Brayman Hackel and Catherine E. Kelly (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 218.

8 Stabil, “Female Curiosities,” 220-221.

9 Premo, “The Old Age of Deborah Norris Logan,” 95.

11 Premo, “The Old Age of Deborah Norris Logan,” 99.

Barr, Marleen. “Deborah Norris Logan, Feminist Criticism, and Identity Theory: Interpreting A Woman’s Diary Without The Danger of Separatism.” Biography 8, no. 1 (1985): 12-24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23539019

Logan, Deborah Norris. Deborah Norris Logan diaries, 1815-1839. From Historical Society of Pennsylvania, The Logan Family Papers, 1638-1964. Accessible via In Her Own Right database.

Premo, Terri L. “’Like a Being Who Does Not Belong’”: The Old Age of Deborah Norris Logan.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 107, no. 1 (1983): 85-112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20091741

Stabile, Susan M. “Female Curiosities: The Transatlantic Female Commonplace Book.” In Reading Women: Literacy, Authorship, and Culture in the Atlantic World, 1500-1800, edited by Hedi Brayman Hackel and Catherine E. Kelly, 217-243. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.